Why big-city bike lane lessons (spoiler: they tend to boost local businesses) may still apply to small towns

There are numerous studies showing the positive (or neutral) economic benefits of creating safe bike/pedestrian infrastructure. However, in the context of small cities, the most common reaction is that they do not apply to small (college) towns because they were conducted in big cities like Berlin, Toronto, New York, etc.

Here, I’d like to argue that they still matter and we shouldn’t simply disregard the consensus evidence, using the W Main corridor of Charlottesville, VA as a case study.

First, the results consistently indicate either positive or neutral impacts across many cities. A review of 23 studies by Volker & Handy reports that:

creating or improving active travel facilities generally has positive or non-significant economic impacts on retail and food service businesses abutting or within a short distance of the facilities, though bicycle facilities might have negative economic effects on auto-centric businesses.

Another multi-city evaluation report (14 corridors across six cities) also founds either positive or non-negative effects on sale and employment.

Some of the other studies not included in this review:

- Salt Lake City saw a boost in economic activity with a removal of parking & safe bike infrastructure.

- City of Cambridge (UK) observed no negative impact of bike lanes.

Even if not all studies are applicable, there’s a dearth of evidence pointing the other way. To argue that a smaller town requires a totally different approach, given the pretty strong consensus, I think there should be at least some evidence other than saying that “they don’t apply here”.

Second, not all studies are about hyper-dense cities like New York and Toronto. Some of the studies included in the aforementioned review or other examples are smaller, not exactly “dense”, cities, such as Davis, CA (with a population of 67k), Victoria, BC (92k), Memphis, Indianapolis, Cambridge (UK), Salt Lake City (again, not a hyper-dense mega city), etc. All of these studies show either neutral or positive impacts.

Third, even in small cities, some of the primary corridors are densely populated and carry substantial traffic, making them comparable to the big-city corridors that have been more extensively studied.

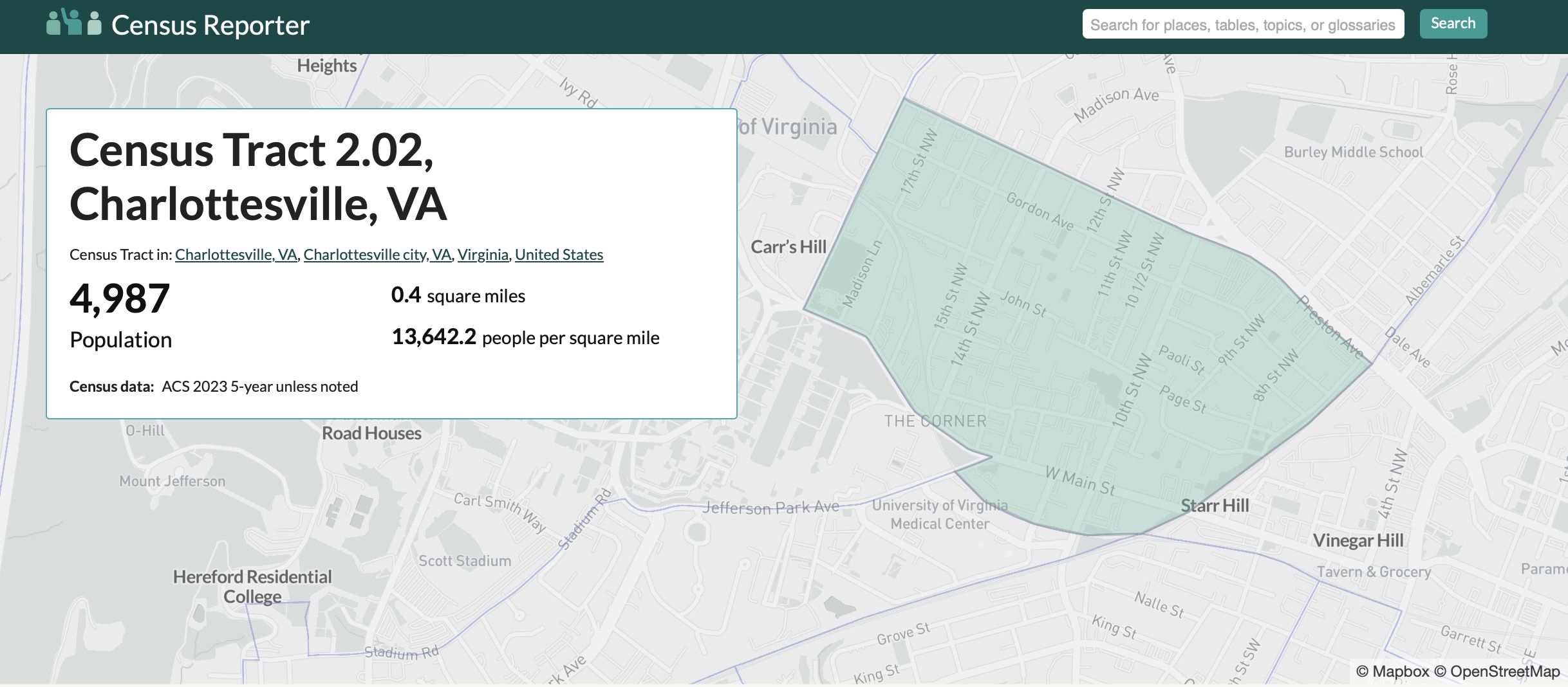

For instance, in the case of Charlottesville, VA, The Census Tract 2.02 that contains the “corner” and W Main st shows that its density is 13,642 people per square mile.

That’s dense!

In fact, this is much denser than the corresponding region studied in Davis, CA (less than 10k people per square mile), and even denser than the corridors in the Indianapolis study.

The Indianapolis study estimated the impact of improvements in Virginia Ave and Mass Ave by comparing them with control corridors, and the estimated economic impact turned out to be positive. The Census Tract 3562 that contains the Virginia Ave in Indianapolis has only 7,180 people per square mile, which is like the half of W Main Census Tract. The Mass ave is comparable to W Main Census Tract, but still sparser. 3542.01 has the density of 12,147, 3542.02 has the density of 10,091.

In other words, the total population of a city is not a good indicator of the density, especially for the main corridors that we often consider putting a good bike infrastructure. A small college town can have a much denser corridors with heavy foot/bike/vehicle traffic that surpass that of much larger cities.

Fourth, the fact that studies done in bigger cities consistently show non-negative impacts may mean smaller cities can expect potentially bigger benefits because there are more reasons to expect negative outcomes from parking removal or bike infrastructure in larger cities. For instance, Indianapolis has a very low bike or walk commute share. If parking removal and bike-lane installation were truly damaging to corridor retail, a larger, car-oriented city like Indianapolis—with far more latent drivers to displace—should have shown stronger negative effects; instead, outcomes were positive.

Nearly ten times more people can reach Indianapolis’s Mass Ave and Virginia Ave corridors by car if we compare the metro population (~2.0 million vs. 200k). Indianapolis residents rely far more on car access. Yet studies show they experienced no economic harm while experiencing some economic benefits.

By comparison, Charlottesville’s West Main corridor is denser, more walkable, and connects major anchors (UVA and Downtown), suggesting that the similar, well-executed improvements are likely produce even more positive results.

In summary, I wanted to highlight the fact that,

- Not all bike lane studies were done in mega-cities with already decent public transit and other infrastructure

- There exists a fairly strong consensus regarding the positive (or at least neutral) benefits of bike infrastructure

- Even the studies done in big cities may be much more translatable than one might think given that small cities can have surprisingly high density.

(share your thoughts on bluesky)